This refelction started out as an exploration of the biases built into AI — how algorithms like ChatGPT inevitably feed us stereotypes, reflecting the collective consciousness of the internet, especially when it comes to entrepreneurship. But as I was writing, I realized the story I was telling wasn’t just about AI. It became a story about the stereotypes entrepreneurs themselves carry, and how those perceptions shape who we become.

It’s a chicken-and-egg scenario: we live the stereotypes we grow up with, and AI reflects those same stereotypes back to us, reinforcing them further. And the way we use AI — for example, through ChatGPT when brainstorming ideas, or Google’s autocomplete when searching for business advice, or even LinkedIn’s algorithm when suggesting who to follow — subtly yet powerfully shapes our perception of what entrepreneurship looks like, who succeeds, and where innovation happens.

Without questioning what we believe about ourselves and others, we risk creating a feedback loop that becomes harder and harder to break.

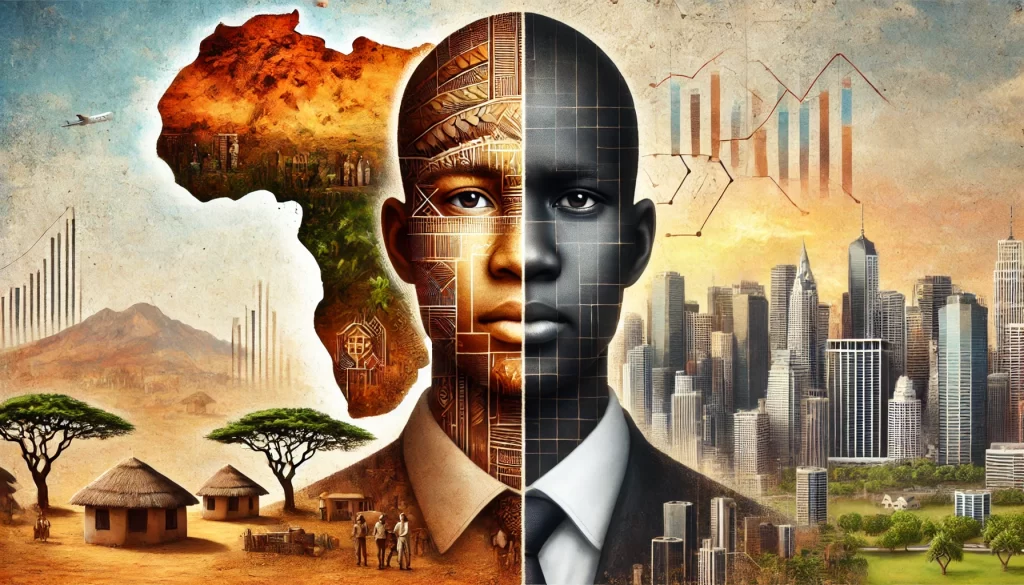

To illustrate how these biases shape reality, let’s step into the shoes of two aspiring entrepreneurs (co-created with ChatGPT 🫣) — one from Kenya and one from the US. Here’s how ChatGPT sees they see the world as they prepare to start their businesses…

“Starting a business in Kenya is… tough. Everyone says that. And I believe it, because I live it. I know that here, success depends more on who you know than what you know. I know that access to capital is nearly impossible unless you have connections or collateral — two things most of us don’t have. I know that when you start a business here, it’s not about scaling up or creating the next big thing. It’s about survival, about finding a way to make ends meet in a system that isn’t built to support you.

I can’t help but think sometimes… what if I had been born an entrepreneur in the United States? Over there, people get funding from venture capitalists just by having a good idea. Over there, businesses grow because the system encourages innovation — not just hustling for survival. I imagine what it would be like to pitch an idea and get investors who believe in the vision, instead of having to explain to people why your business isn’t just another hustle. In the United States, they don’t have to worry about power outages disrupting their operations or clients not paying for months. They have systems. They have access. They have opportunities.”

“Starting a business in the US? People think it’s all about pitching to VCs, getting millions in funding, and launching the next tech unicorn. But that’s Silicon Valley, not Main Street. Sure, we have venture capitalists — but 99% of entrepreneurs never get a meeting with one, let alone funding. Most of us bootstrap, just like you do. We max out credit cards, borrow from friends, and hustle to keep things afloat. And the market here? It’s saturated. Whatever business you’re thinking of starting, there are already ten others doing it — probably better funded, with a bigger team, and a stronger brand. It’s brutal competition, and scaling isn’t automatic. The US has systems, yes — but systems are expensive. Finding customers? You’re up against companies with million-dollar budgets.

I sometimes think what it must be like to be an entrepreneur in Kenya — a place where markets aren’t as saturated, where there’s room for new ideas and less corporate monopoly.”

What’s striking here is that both the Kenyan and American perspectives, despite their differences, are shaped by the same larger-than-life archetype: the Silicon Valley entrepreneur. The startup culture of hyper-growth, venture capital, and global disruption has become the default mental model for what entrepreneurship “should” look like — whether you’re in Nairobi or Chicago. And that’s where the biggest stereotype of all lives.

But here’s where things get tricky:

- The leap from stereotypes to AI feedback loops: The moment we ask AI to “explain entrepreneurship in Kenya” or “describe what it’s like to start a business in the US,” we trigger a cascade of assumptions. AI doesn’t invent stereotypes; it mirrors what’s already out there. The more we seek validation for what we think we know, the more these stereotypes harden into what feels like objective truth. This is how biases evolve into feedback loops — the story we believe becomes the story AI reflects, and the reflection reinforces the belief.

- The risk of a circular argument: If we aren’t careful, we end up in a loop where both human perceptions and AI-generated insights keep pointing to the same conclusions. Kenyans may see the US as a land of unlimited opportunity and Americans may romanticize the Kenyan entrepreneurs to have true impact, and AI — pulling from oceans of existing content — affirms both narratives. The danger is that this cycle makes it harder to question the validity of the stereotypes in the first place. And when stereotypes go unchallenged, they shape behaviour, which in turn, shapes reality.

What’s most revealing here is that, despite the different starting points, both the Kenyan and American entrepreneurs in this story share the same underlying reality: building a business is hard, access to funding is scarce, and the challenges of getting started are universal. But the stories we tell ourselves about what’s possible — and where — determine how we approach that reality.

So when AI tools like ChatGPT reflect back to us what “entrepreneurship” means, they’re reflecting this globalized Silicon Valley narrative — amplifying it for American entrepreneurs, while making it feel even more out of reach for Kenyan entrepreneurs.

And that’s the danger. If we’re not careful, we’ll keep reinforcing these myths until they feel like reality. The challenge for entrepreneurs — and for the AI tools we build and use — is to question these narratives, to see beyond them, and to create new stories that reflect the messy, inspiring, and deeply human realities of starting a business anywhere in the world.

What we believe shapes what we build. And in the age of AI, what we build shapes what we believe. Let’s make sure that cycle is one of empowerment, not limitation.